On January 4, 2021, I resigned as Director of Faith Formation at the Saint Clare of Assisi Catholic Church on Daniel Island, in Charleston, South Carolina. I began in the position in July 2019, moving my family from our home in Colorado where we had lived for fourteen years. Only months into what I had anticipated as an opportunity to work in deeply mystagogical ways with adults, children, and their families, I discovered barriers in worship and patterns of spirituality that spoke to larger issues in that parish, and in the Catholic Church in general, that needed to be addressed.

As I undertook to identify those issues fully and to work with our pastor and other staff members to develop an integrated approach to address them, I ran into a morass of hidden agendas, attempts to silence and redirect the narrative, and the surprising complexities of debate and division within the Catholic world that were deeply affecting our young parish. I discovered as well, through the insights of a former member of the pastoral council who had also been part of my interview team, that concerned parish leaders had hoped I would become a champion for voices in the parish who had attempted and failed to address the challenges of pastoral leadership, liturgical collapse, and ministry fragmentation we continued to face.

What follows is a summary of my approach to the problems I discovered along with additional observations that led to my resignation.

Late October 2019, our priest announced his plans to shift to ad orientem in the mass during Advent. (Ad orientum is the facing of both priest and congregation to the East during the Eucharistic celebration that results in the priest’s back to the people. For some, such an orientation embodies a sense of the transcendence of God and is desirable for those seeking a return to ‘traditional’ Catholic worship, often based on a misunderstanding of the origins of the practice. For more about ad orientum, please see https://themystagogue.org/?p=192.) I began to explore why he wanted to make that change and the reasons I and others felt so strongly that we should not. Not long into that effort, I realized that we were wrestling with that particular issue without the advantage of a clear sense of our identity and purpose as a parish—without a clear vision—and that we had an opportunity to discover both deeper issues and potential in the body life of our community.

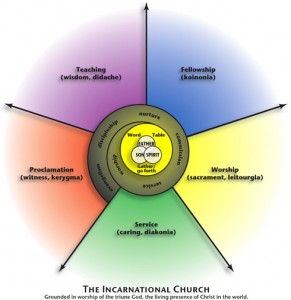

Very quickly my attention shifted, as I explained in the ensuing document, to an attempt “to evaluate all aspects of parish life such that we would have a basis from which to find a way forward, as a staff, to help develop Saint Clare of Assisi Catholic Church into that vibrant, kerygmatic community in which all comers can encounter and grow into a profound and fruitful relationship with Jesus Christ” (“Considerations for Building the Body of Christ” aka “Thoughts Moving Forward”). I began sharing versions of that evolving evaluation with our pastor in December 2019 with the hope that we would use it as a basis for discussion and planning as a staff. Sadly, he cautioned me not to share it with other staff members and for a long time failed to respond directly the the concerns and suggestions it contained, which included a very personal appeal to recognize the urgency to address the issues with clarity.

In my role, I explained, I had received a great deal of feedback during my short time in the parish. Some had been very positive, and all had been offered by those who clearly care about our parish and its impact. I discovered that many were deeply alarmed by the direction we took in the mass and ways our worship impacted the vitality and effectiveness of other aspects of our identity and mission. The potential shift to ad orientem was only one of the small but impactive things I witnessed that appear to deny the inclinations I believed the Holy Spirit had developed in our parish and that demonstrated an undefined but active agenda that worked against our ability and desire to fulfill our calling as the body of Christ. As I listened and observed, I worked to look as objectively and yet realistically as possible at the parish out of my own experience and training while making every effort to assure others who had brought their concerns that we had good things to celebrate and build on, even as we looked to confront and correct those things that needed attention.

The concerns were significant enough, though, that there was urgency in the need to address them. Many of our staff also desired to have opportunity to discuss those concerns and to seek a way forward that could result in a revitalization of our ministry at Saint Clare, and it was their sense that we had not addressed them directly or adequately that appeared to have played a role in the resignation of several staff members, including my predecessor, our previous music and liturgy director, and most recently, our coordinator of children’s ministries.

I indicated that I was deeply concerned myself. “Because our worship is the heart of the church, the very embodiment of her identity and mission from which both are derived and empowered,” I wrote, “the concerns related to the mass are those that need to be addressed most urgently” (“Considerations”). Putting my level of concern in very personal terms, I continued,

A parish can survive for a long time while remaining entrenched in forms and practices that are not ideal, but worship that risks stifling the Holy Spirit and dampening the joy and expression of God’s people can too easily become a slow death for a community that is struggling to demonstrate to its members and to the world the compelling love of Christ and the joy of serving him.

I must confess that such a risk as I have seen it at Saint Clare has become for me something of a crisis of faith and mission. When I interviewed, my impression was that Saint Clare was in many ways appropriately progressive in terms of her formation efforts, willing to learn and try approaches that are not typical in the Catholic world. I found that to be true in many ways, and I have enjoyed the flexibility to further evolve those efforts and to find glimpses that our work has been effective and well-received. But I was wrong to think the worship at Saint Clare was equally forward-looking and discovered quickly that the Catholic Church, from this vantage, looks very different than the one I and my famliy came to call home. I felt called to be a part of Saint Clare, but even as my professional concern grew at the signs of incongruity between our worship and the vitality for which we long in our parish, I became alarmed to find that I was questioning my place in the church and whether or not the reality I was seeing was more indicative of the church’s true identity than what I had known of the church before coming to Charleston.

I am praying for a renewal of the sense that the Catholic Church is the place in which I can worship and serve with confidence that she embodies the gospel in the best possible way. I am praying especially that Saint Clare becomes a parish in which I can continue to serve with genuine passion and the hope that we are all working together to discover what Christ desires us to be. Even as I write this, I am still worried that I have to be too guarded in the ways I present the concerns I have mentioned and others have brought. I feel the need to describe them with weight befitting their significance but with tact that keeps the criticism from appearing too severe. That I have to tread so carefully is a concern itself that I pray is unfounded, but I do hope it is perceived as a desire to build on what is good and to find constructive ways to examine and evolve those things that can become a rich and healthy foundation to all aspects of our life and ministry as the body of Christ. (“Considerations”)

One element of disquiet I never thought I would encounter had been the capitulation of the church (culture as well) to the minor threat of the coronavirus. Rather than continuing to worship the Lord of all creation, boldly approaching the throne of grace and demonstrating to all the world that what we believe is true, about Christ, about his active and potent presence in our worship, about his sacramental gift of himself in the mass, about his call to enter suffering and death with the confidence in his promise to save all things through death and resurrection, we declared through our actions that suffering and death are to be feared and avoided. Even apart from consideration of Christ, a reasonable and measured response to the reality of any threat was nowhere to be found. In that absence, the church could and should have proclaimed by its worship the hope of Jesus, rooted in the very source of redemption and healing.

And all of this was in the face of a threat that was, quite frankly, less potent than many humankind has faced and still faces in the course of life in a fallen world. We had enough evidence to suggest that the ‘safe’ practices in which we engaged were not really going to mitigate the virus (they might have delayed some from getting it, but it will always be around). At the same time, even with surges in infection, the death rate had dropped by more than 60% since June (and continued to drop such that it was a fallacy to suggest that death is common). More and more evidence challenged the ‘accepted’ narrative that this virus was worse than the flu and other related illnesses, and we had imposed as much harm as we helped through the restrictions. The church, including our own parish, capitulated to fear, culture, and even to insurance companies over Christ himself, undermining the truth we claim by our actions. Our own worship with masks and elimination of critical elements, such as the peace, the blood of Christ, and communion within the mass (as we did for a time), was not really the worship of a people confident in the grace and mercy of our Lord.

For me, this capitulation added to my concerns about the church and my participation in it. For those for whom we were responsible, we further obscured the presence and activity of the Holy Spirit and deepened the urgency to restore the integrity of our worship, the authenticity of our hope in the present and future kingdom of God, and the joy of knowing and serving the Lord of all creation, in season and out of season, even when it runs counter to the prevailing narratives of fear and isolation. To the world that saw the minor threat as apocalypse and retreated behind presumptions of a facile social ‘unity’, fleeting ‘protection’, and false ‘compassion’, the church could have proclaimed the depth of grace, mercy, and salvation in the face of all threats with the courage of the redeemed in Christ who do not fear to risk everything, even health and safety, to proclaim Christ and the hope of the new creation.

As I explored these and other concerns in the document I came to call “Thoughts Moving Forward” and asked for our pastor’s help in exploring them as a staff, I watched my own family and others withdraw from worship and parish life in ways that betrayed their disillusionment with the church and its ability to embody the joy of the gospel and an abiding faith in our Lord reflected in all we are and do as the people of God, a living sacrament of his kingdom. My wife and sons, like many in the parish, began to yearn for life-giving evidence of the presence of the Spirit in the church and expressed again and again that we were not going to find it at Saint Clare. Even as I struggled myself, I watched them sink deeper into depression and apathy to the point where I felt we would have to go elsewhere to rediscover the presence of Christ and the joy of serving him.

After nine months and our pastor’s caution not to share the evaluation with anyone else, he finally made an overture to explore the concerns I had been raising, and I saw his visit in August 2020 over dinner a glimmer of hope that we might begin that process of discussion, even as a staff, that might help us openly and honestly develop a vision for mission and ministry that might revitalize our parish and restore the joy for which we had been yearning. That hope has quickly faded, as he did not followed though with the time and attention he promised to give to those concerns nor the pastoral care I thought he might extend to my family and to all who shared their own concerns with me through the previous year. In fact, that hope dissipated altogether as I witnessed more small, but potent, signs of an unarticulated agenda that I believed ran counter to the work of the Spirit that triggered the concerns of people in the parish who were hungry for worship and leadership that courageously embodies the challenge and joy of the gospel. I also witnessed a tendency towards historical and theological revisionism, both in some of the curriculum that we used from popular Catholic sources (Ascension Press’ Epic: The Early Church series especially) and in our pastor’s desire to continue to use that curriculum, as well as from comments he made in classes he led, in homilies, and in other contexts. Such things belied the truth we presumed to proclaim.

Until July 2020, our pastor had been leading two parishes, which is certainly not easy, especially as he was also handling a building program in one parish and a restoration program in the other. Some of the concerns I mentioned also related to issues of leadership and vision beyond the parish. I was surprised to discover, though, that both taking on the second parish, Saint Mary of the Annunciation in Charleston, and building in the more elaborate, expensive style (the gothic cathedral), were made over the objections of concerned voices in the parish, including those serving as leaders on our councils. I came to see both, especially the building program, as analogous to the way the Catholic Church has in many ways obscured the very gospel and the apostolic faith she claims to preserve and embody. Although he resigned as pastor of Saint Mary’s, we did not witness a renewed vigor in pastoral leadership at Saint Clare, although the building program received a great deal of time and attention. As it continued to evolve under his careful and energetic guidance, still to the detriment of other ministry, it too impeded rather than advanced our call to embody the mission of the body of Christ.

As I watched the costs of the building balloon from the astounding to the ridiculous even as its value to the mission of our parish diminished, I began to despair that the values espoused by our Lord, values we had been trying desperately to reflect in our ministry in formation and evangelism in the parish, would ever fully define our priorities or find expression and foundation in the worship of our local community. As the costs skyrocketed, many compromises were made to the plans, including a significant reduction in the number of pews it could accommodate. The parish would have a beautiful building, but its reduced capacity would mean fewer opportunities to worship together as a body, especially at those times like Christmas and Easter when more than usual would hope to attend. Also missing would be the spaces necessary for robust formation programs and gatherings outside of the mass, not to mention facilities that I hoped would one day support mission-minded service ministry, as they were shunted to latter phases.

One of the biggest barriers to consistency in our formation and evangelism efforts had been a difficult and often contentious relationship with Bishop England High School, where we had been sharing autitorium and classroom space. At its best, that relationship left us with less than ideal access to facilities and imposed a significant burden on staff and volunteers to facilitate ministry. The additional space afforded by larger administrative offices into which we moved in June 2019, while helpful, remained limited and expensive. I came to fear that increased debt and the burden of maintaining both a new building and the continuing expenses of office and classroom space not addressed in the first phase of construction would significantly delay our ability to address those needs. The beautiful building would, in its inadequacy, perpetuate barriers to mission in the local parish, even as the worship space, clearly designed to support “traditional” forms and aesthetics rooted in more medieval than apostolic norms, would continue to obscure the vitality of worship that is dynamic, compelling, and life-giving.

The edifice of transcendent beauty that emphasizes solemnity and ‘tradition’ over joy and mission seemed to me to parallel the all-too-rigid edifice of presumed infallibility of the truth of the Church that has dimmed the light of the gospel in much of the Catholic faith. The concerns I raised at what I witnessed at Saint Clare drove a renewed urgency in my studies of the Fathers and divines Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant, and I came to the realization that the restored communion of the one, holy, apostolic church would require as much humble reform of the Catholic Church—even through honest reexamination of the hitherto unassailable magisterium—as the submission we often expect of our ‘separated brethren’. The Catholic Church has begun in recent decades to rediscover some of the essential nature of the gospel and our call to mission, which is what brought me and my family to her nearly nine years ago, but it continues to struggle under a great deal of baggage codified and blessed as ‘apostolic’ that is not and that has made that rediscovery falter. The fullness of truth is found not in the Catholic Church but in the gospel of our Lord to which we must again submit all assumptions of ‘Sacred Tradition’, seeking with our brothers and sisters in the truly universal (catholic) church the unobscured, foundational truth of the Spirit of God who challenges all of his people to bear the joy and grace of Jesus Christ to a fallen world. With Pope Francis, I came to “dream of a ‘missionary option’, that is, a missionary impulse capable of transforming everything, so that the Church’s customs, ways of doing things, times and schedules, language and structures can be suitably channeled for the evangelization of today’s world rather than for her self-preservation” (Evangelii Gaudium, 27). His radical, call is, I firmly believed, the call of Christ himself to his church.

The renewal of structures demanded by pastoral conversion can only be understood in this light: as part of an effort to make them more mission-oriented, to make ordinary pastoral activity on every level more inclusive and open, to inspire in pastoral workers a constant desire to go forth and in this way to elicit a positive response from all those whom Jesus summons to friendship with himself. As John Paul II once said to the Bishops of Oceania: “All renewal in the Church must have mission as its goal if it is not to fall prey to a kind of ecclesial introversion.” (EG, 27)

In her ongoing discernment, the Church can also come to see that certain customs not directly connected to the heart of the Gospel, even some which have deep historical roots, are no longer properly understood and appreciated. Some of these customs may be beautiful, but they no longer serve as means of communicating the Gospel. We should not be afraid to re-examine them. At the same time, the Church has rules or precepts which may have been quite effective in their time, but no longer have the same usefulness for directing and shaping people’s lives. Saint Thomas Aquinas pointed out that the precepts which Christ and the apostles gave to the people of God “are very few.” Citing Saint Augustine, he noted that the precepts subsequently enjoined by the Church should be insisted upon with moderation “so as not to burden the lives of the faithful” and make our religion a form of servitude, whereas “God’s mercy has willed that we should be free.” This warning, issued many centuries ago, is most timely today. It ought to be one of the criteria to be taken into account in considering a reform of the Church and her preaching which would enable it to reach everyone. (EG, 43)

I was convinced that rather than a conviction that she embodies in perfection the apostolic tradition, the Catholic Church needs to see herself more as the disciple still seeking that truth and willing to submit all she has learned and become to the refining scrutiny of the Spirit that leads her to a maturity yet to be realized. Again, as Pope Francis perceptively argues,

The Church is herself a missionary disciple; she needs to grow in her interpretation of the revealed word and in her understanding of truth. It is the task of exegetes and theologians to help “the judgment of the Church to mature.” The other sciences also help to accomplish this, each in its own way. With reference to the social sciences, for example, John Paul II said that the Church values their research, which helps her “to derive concrete indications helpful for her magisterial mission.” Within the Church countless issues are being studied and reflected upon with great freedom. Differing currents of thought in philosophy, theology and pastoral practice, if open to being reconciled by the Spirit in respect and love, can enable the Church to grow, since all of them help to express more clearly the immense riches of God’s word. For those who long for a monolithic body of doctrine guarded by all and leaving no room for nuance, this might appear as undesirable and leading to confusion. But in fact such variety serves to bring out and develop different facets of the inexhaustible riches of the Gospel. (EG, 40)

The deep and life-giving truth of God extends beyond the Catholic Church and her magisterium, and I saw in Vatican II and in the leadership of recent leaders a sensitivity to that reality when I entered the Catholic Church. I did not agree with everything Pope Francis has done and said, but I found in him and other recent popes a willingness to think anew about the challenges the gospel presents to the church and the willingness to submit everything to our risen Lord in an effort to reform and refocus all we are and do with God’s redemptive mission at the center. I struggled to find that same willingness in our leadership at Saint Clare.

I encountered it in some of our people, and I worked to support and equip them as much as possible. I witnessed in some of our most engaged members, who worked often in partial and uncoordinated efforts, a laudable desire to push the boundaries of tradition and expectation for the sake of the gospel. Until a clear vision built around the joy of knowing Jesus and inviting others to do the same, with great risk to ourselves and the comfort of our Catholic ‘culture’, permeated our worship and sacramental life, our stewardship and building programs, and all of our formation efforts, formal and informal, those partial and isolated efforts would falter.

Even as I resigned, I prayed that vision would develop and bear fruit at Saint Clare, but my hope that it would had dimmed. I have spent most of my adult life preaching and teaching the truth of the gospel, often at great cost to livelihood and security and very often challenging the traditions of the faith to which I have belonged. I found some fulfillment in doing so at Saint Clare and some in the parish hungry and receptive to a deeper call to realize the mission of Christ, but I also encountered the need to compromise what I have learned to be the truth of Christ and the hope of the new creation to an extent that put me at odds with the vision of the church our pastor and others, some of the staff included, appeared to embrace. While I struggled to remain faithful to our Lord in asking our pastor to explore reform in our community, I found many of those efforts marginalized, and I came to realize that I could not stay while I watch hope fade in my own family and others who care most deeply in the parish.